Each PyQt widget, which is derived from QObject class, is designed to emit ‘ signal ’ in response to one or more events. The signal on its own does not perform any action. Instead, it is ‘connected’ to a ‘ slot ’. The slot can be any callable Python function. Number 1 & 2 are available for Python slot, while number 2 & 3 are available for QT slot. It is clear that besides QT predefined slot, any python callable function/methods is qulified to be a Python slot. These points are made in Summerfield's article on Signals and Slots. Old style qt signal & slot VS new style qt singal & slot.

- In this file we can import the Python class generated by the pyuic5 command. We can also add our custom slots in this file. This practice of separating Qt Desginer code from custom code is good Qt programming practice. It has been suggested in Section 3 of the video ebook: 'Python GUI Programming Recipes using PyQt5'.

- QtCore.SIGNAL and QtCore.SLOT macros allow Python to interface with Qt signal and slot delivery mechanisms. This is the old way of using signals and slots. The example below uses the well known clicked signal from a QPushButton. The connect method has a non python-friendly syntax.

This PyQt5 tutorial shows how to use Python 3 and Qt to create a GUI on Windows, Mac or Linux. It even covers creating an installer for your app.

What is PyQt5?

PyQt is a library that lets you use the Qt GUI framework from Python. Qt itself is written in C++. By using it from Python, you can build applications much more quickly while not sacrificing much of the speed of C++.

PyQt5 refers to the most recent version 5 of Qt. You may still find the occasional mention of (Py)Qt4 on the web, but it is old and no longer supported.

An interesting new competitor to PyQt is Qt for Python. Its API is virtually identical. Unlike PyQt, it is licensed under the LGPL and can thus be used for free in commercial projects. It's backed by the Qt company, and thus likely the future. We use PyQt here because it is more mature. Since the APIs are so similar, you can easily switch your apps to Qt for Python later.

Install PyQt

The best way to manage dependencies in Python is via a virtual environment. A virtual environment is simply a local directory that contains the libraries for a specific project. This is unlike a system-wide installation of those libraries, which would affect all of your other projects as well.

To create a virtual environment in the current directory, execute the following command:

This creates the venv/ folder. To activate the virtual environment on Windows, run:

On Mac and Linux, use:

You can see that the virtual environment is active by the (venv) prefix in your shell:

To now install PyQt, issue the following command:

The reason why we're using version 5.9.2 is that not all (Py)Qt releases are equally stable. This version is guaranteed to work. Besides this subtlety – Congratulations! You've successfully set up PyQt5.

Create a GUI

Time to write our very first GUI app! With the virtual environment still active, start Python. We will execute the following commands:

First, we tell Python to load PyQt via the import statement:

Next, we create a QApplication with the command:

This is a requirement of Qt: Every GUI app must have exactly one instance of QApplication. Many parts of Qt don't work until you have executed the above line. You will therefore need it in virtually every (Py)Qt app you write.

The brackets [] in the above line represent the command line arguments passed to the application. Because our app doesn't use any parameters, we leave the brackets empty.

Now, to actually see something, we create a simple label:

Then, we tell Qt to show the label on the screen:

Depending on your operating system, this already opens a tiny little window:

The last step is to hand control over to Qt and ask it to 'run the application until the user closes it'. This is done via the command:

If all this worked as expected then well done! You've just built your first GUI app with Python and Qt.

Widgets

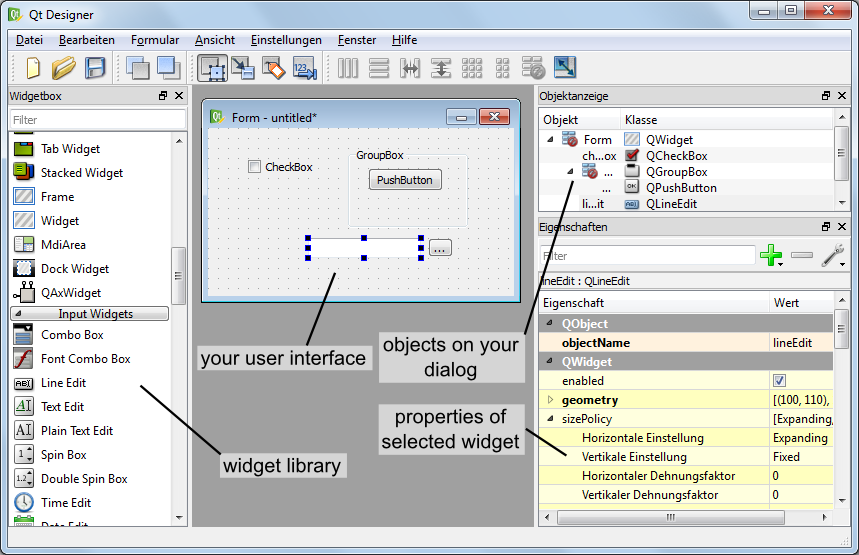

Everything you see in a (Py)Qt app is a widget: Buttons, labels, windows, dialogs, progress bars etc. Like HTML elements, widgets are often nested. For example, a window can contain a button, which in turn contains a label.

The following screenshot shows the most common Qt widgets:

Top-to-bottom, left-to-right, they are:

You can download the code for the app shown in the screenshot here, if you are interested.

Python Qt Slot Decorator

Layouts

Like the example above, your GUI will most likely consist of multiple widgets. In this case, you need to tell Qt how to position them. For instance, you can use QVBoxLayout to stack widgets vertically:

The code for this screenshot is:

As before, we instantiate a QApplication. Then, we create a window. We use the most basic type QWidget for it because it merely acts as a container and we don't want it to have any special behavior. Next, we create the layout and add two QPushButtons to it. Finally, we tell the window to use this layout (and thus its contents). As in our first application, we end with calls to .show() and app.exec_().

There are of course many other kinds of layouts (eg. QHBoxLayout to lay out items in a row). See Qt's documentation for an overview.

Custom styles

One of Qt's strengths is its support for custom styles. There are many mechanisms that let you customize the look and feel of your application. This section outlines a few.

Built-in styles

The coarsest way to change the appearance of your application is to set the global Style. Recall the widgets screenshot above:

This uses a style called Fusion. If you use the Windows style instead, then it looks as follows:

To apply a style, use app.setStyle(...):

The available styles depend on your platform but are usually 'Fusion', 'Windows', 'WindowsVista' (Windows only) and 'Macintosh' (Mac only).

Custom colors

If you like a style, but want to change its colors (eg. to a dark theme), then you can use QPalette and app.setPalette(...). For example:

Python Qt Slots

This changes the text color in buttons to red:

For a dark theme of the Fusion style, see here.

Style sheets

In addition to the above, you can change the appearance of your application via style sheets. This is Qt's analogue of CSS. We can use this for example to add some spacing:

For more information about style sheets, please see Qt's documentation.

Signals / slots

Qt uses a mechanism called signals to let you react to events such as the user clicking a button. The following example illustrates this. It contains a button that, when clicked, shows a message box:

The interesting line is highlighted above: button.clicked is a signal, .connect(...) lets us install a so-called slot on it. This is simply a function that gets called when the signal occurs. In the above example, our slot shows a message box.

The term slot is important when using Qt from C++, because slots must be declared in a special way in C++. In Python however, any function can be a slot – we saw this above. For this reason, the distinction between slots and 'normal' functions has little relevance for us.

Signals are ubiquitous in Qt. And of course, you can also define your own. This however is beyond the scope of this tutorial.

Compile your app

You now have the basic knowledge for creating a GUI that responds to user input. Say you've written an app. It runs on your computer. How do you give it to other people, so they can run it as well?

You could ask the users of your app to install Python and PyQt like we did above, then give them your source code. But that is very tedious (and usually impractical). What we want instead is a standalone version of your app. That is, a binary executable that other people can run on their systems without having to install anything.

In the Python world, the process of turning source code into a self-contained executable is called freezing. Although there are many libraries that address this issue – such as PyInstaller, py2exe, cx_Freeze, bbfreze, py2app, ... – freezing PyQt apps has traditionally been a surprisingly hard problem.

We will use a new library called fbs that lets you create standalone executables for PyQt apps. To install it, enter the command:

Then, execute the following:

This prompts you for a few values:

When you type in the suggested run command, an empty window should open:

This is a PyQt5 app just like the ones we have seen before. Its source code is in src/main/python/main.py in your current directory. But here's the cool part: We can use fbs to turn it into a standalone executable!

This places a self-contained binary in the target/MyApp/ folder of your current directory. You can send it to your friends (with the same OS as yours) and they will be able to run your app!

(Please note that fbs currently targets Python 3.5 or 3.6. If you have a different version and the above does not work, please install Python 3.6 and try again. On macOS, you can also install Python 3.5 with Homebrew.)

Bonus: Create an installer

fbs also lets you create an installer for your app via the command fbs installer:

(If you are on Windows, you first need to install NSIS and place it on your PATH.)

For more information on how you can use fbs for your existing application, please see this article. Or fbs's tutorial.

Summary

If you have made it this far, then big congratulations. Hopefully, you now have a good idea of how PyQt (and its various parts) can be used to write a desktop application with Python. We also saw how fbs lets you create standalone executables and installers.

Due to the popularity of this article, I wrote a PyQt5 book.

The book explains in more detail how you can create your own apps. Even Phil Thompson, the creator of PyQt, read the book and said it's 'very good'. So check it out!

Michael has been working with PyQt5 since 2016, when he started fman, a cross-platform file manager. Frustrated with the difficulties of creating a desktop app, Michael open sourced fman's build system (fbs). It saves you months when creating Python Qt GUIs. Recently, Michael also wrote a popular book about these two technologies.

This page describes the use of signals and slots in Qt for Python.The emphasis is on illustrating the use of so-called new-style signals and slots, although the traditional syntax is also given as a reference.

The main goal of this new-style is to provide a more Pythonic syntax to Python programmers.

- 2New syntax: Signal() and Slot()

Traditional syntax: SIGNAL () and SLOT()

QtCore.SIGNAL() and QtCore.SLOT() macros allow Python to interface with Qt signal and slot delivery mechanisms.This is the old way of using signals and slots.

The example below uses the well known clicked signal from a QPushButton.The connect method has a non python-friendly syntax.It is necessary to inform the object, its signal (via macro) and a slot to be connected to.

New syntax: Signal() and Slot()

The new-style uses a different syntax to create and to connect signals and slots.The previous example could be rewritten as:

Using QtCore.Signal()

Signals can be defined using the QtCore.Signal() class.Python types and C types can be passed as parameters to it.If you need to overload it just pass the types as tuples or lists.

In addition to that, it can receive also a named argument name that defines the signal name.If nothing is passed as name then the new signal will have the same name as the variable that it is being assigned to.

The Examples section below has a collection of examples on the use of QtCore.Signal().

Note: Signals should be defined only within classes inheriting from QObject.This way the signal information is added to the class QMetaObject structure.

Using QtCore.Slot()

Python Qt Signal Slot

Slots are assigned and overloaded using the decorator QtCore.Slot().Again, to define a signature just pass the types like the QtCore.Signal() class.Unlike the Signal() class, to overload a function, you don't pass every variation as tuple or list.Instead, you have to define a new decorator for every different signature.The examples section below will make it clearer.

Another difference is about its keywords.Slot() accepts a name and a result.The result keyword defines the type that will be returned and can be a C or Python type.name behaves the same way as in Signal().If nothing is passed as name then the new slot will have the same name as the function that is being decorated.

Examples

The examples below illustrate how to define and connect signals and slots in PySide2.Both basic connections and more complex examples are given.

- Hello World example: the basic example, showing how to connect a signal to a slot without any parameters.

- Next, some arguments are added. This is a modified Hello World version. Some arguments are added to the slot and a new signal is created.

- Add some overloads. A small modification of the previous example, now with overloaded decorators.

- An example with slot overloads and more complicated signal connections and emissions (note that when passing arguments to a signal you use '[]'):

- An example of an object method emitting a signal:

- An example of a signal emitted from another QThread:

- Signals are runtime objects owned by instances, they are not class attributes: